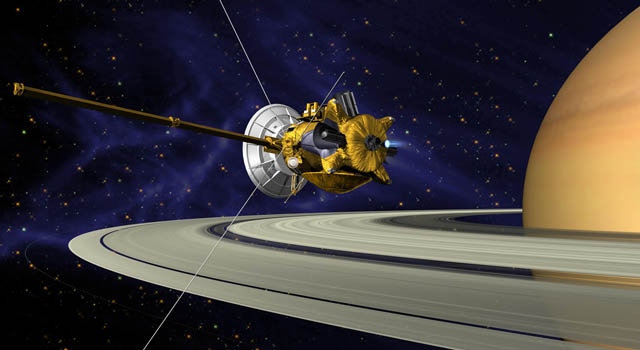

Artist’s concept of NASA’s Cassini spacecraft at Saturn.

Credit: NASA/JPL

The Cassini-Huygens spacecraft has been orbiting Saturn since 2004. The mission is known for discoveries such as finding jets of water erupting from Enceladus, and tracking down a few new moons for Saturn. Now low on fuel, the spacecraft will make a suicidal plunge into the ringed planet in 2017 and capture some data about Saturn’s interior on the way. (This will avoid the possibility of Cassini some day crashing on to a potentially habitable icy moon, such as Enceladus or Rhea.)

The ambitious mission is a joint project among several space agencies, which is a contrast from the large NASA probes of the past such as Pioneer and Voyager. In this case, the main participants are NASA, the European Space Agency and Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (the Italian space agency).

Launch and cruise

Cassini didn’t head straight to Saturn. Rather, its mission involved complicated orbital mechanics. It went past several planets — including Venus (twice), Earth and Jupiter — to get a speed boost by taking advantage of each planet’s gravity.

The nearly 12,600-lb. (about 5,700 kilograms) spacecraft was hefted off of Earth on Oct. 15, 1997. It went by Venus in April 1998 and June 1999, Earth in August 1999 and Jupiter in December 2000.

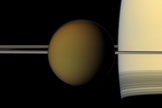

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, passes in front of the planet and its rings in this true color snapshot from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. This view looks toward the northern, sunlit side of the rings from just above the ring plane. It was taken on May 21, 2011, when Cassini was about 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) from Titan.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

There were some on Earth who were concerned that Cassini’s pass by Earth would be risky, given that the spacecraft was carrying radioisotope thermoelectric generators (nuclear power) on board. These generators are commonly used for NASA missions.

NASA responded by issuing a supplementary document about the flyby and detailing the agency’s methodology for protecting the planet, saying there was less than a one-in-a-million chance of an impact occurring.

Cassini safely flew by, and after taking a pass by Jupiter settled into orbit around Saturn on July 1, 2004. Among its prime objectives were to look for more moons, to figure out what caused Saturn’s rings and the colors in the rings, and understanding more about the planet’s moons.

Perhaps Cassini’s most detailed look came after releasing the Huygens lander towards Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Huygens descended through the mysterious haze surrounding the moon and landed on Jan. 14, 2005.

It beamed information back to Earth for nearly 2.5 hours during its descent, and then continued to relay what it was seeing from the surface for 1 hour, 12 minutes.

In that brief window of time, researchers saw pictures of a rock field and got information back about the moon’s wind and gases on the atmosphere and the surface.

Magnificent moons

One of the defining features of Saturn is its number of moons. Excluding the trillions of tons of little rocks that make up its rings, Saturn has 62 discovered moons as of September 2012. NASA lists 53 named moons on one of its websites.

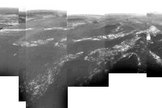

This first panorama of Titan released by ESA shows a full 360-degree view around the Huygens probe. The left-hand side shows a boundary between light and dark areas. The white streaks seen near this boundary could be ground ‘fog’, as they were not immediately visible from higher altitudes. Huygens drifted over a plateau (centre of image) and was heading towards its landing site in a dark area (right) during descent.

Credit: ESA/NASA/University of Arizona.

In fact, Cassini discovered two new moons almost immediately after arriving (Methone and Pallene) and before 2004 had ended, it detected Polydeuces. [Gallery: Latest Saturn Photos from NASA’s Cassini Orbiter]

As the probe wandered past Saturn’s moons, the findings it brought back to Earth revealed new things about their environments and appearances. Some of the more notable findings include:

Saturn has not gone ignored, either. For example, in 2012, a NASA study postulated that Saturn’s jet streams in the atmosphere may be powered by internal heat, instead of energy from the sun. Scientists believe that heat brings up water vapor from the inside of the planet, which condenses as it rises and produces heat. That heat is believed to be behind jet stream formation, as well as that of storms.

Extending the mission

Cassini wrapped up its four-year planned mission in June 2008 and then embarked on the Cassini Equinox mission, which went through to September 2010. During those two years, Cassini flew past Titan 26 times and Enceladus seven times. It also zipped by Dione, Rhea and Helene once.

Now the probe is in the Cassini Solstice Mission, which is intended to last until September 2017. The probe focused on a series of flybys of Saturn’s icy moons, particularly Enceladus and Titan. Saturn’s solstices will come in May 2017, meaning it will be summer in the northern hemisphere and winter in the southern hemisphere.

Because Cassini arrived at Saturn at the last solstice, NASA says this extension will let scientists study seasonal changes in detail at the ringed planet.

Saturn orbits the sun every 29 Earth years. By the time Cassini reaches the end of its extended mission, the spacecraft will have accompanied the planet for about half of that journey.

Additional resource

Let’s block ads! (Why?)

http://www.space.com/17754-cassini-huygens.html Cassini-Huygens: Exploring Saturn's System

[bestandroiddoubledinheadunit950.blogspot.com]Cassini-Huygens: Exploring Saturn’s System

No comments:

Post a Comment